Investing For The Long-term (Retirement)

How to Invest in ETFs, Our Chosen Vehicle

We’ve chosen our main investment vehicle: ETFs. It’s either our only investment vehicle for the long-term or it’s at least our main vehicle if we’re investing in a PPR as well (as discussed above). Now, we’ll choose which ETFs to buy by following the steps below.

First, we’ll pick a market index to track. Again, our investment approach says that “we won’t be able to pick the stocks that will outperform the market, attempting to do so is pretty much gambling, so we’ll just invest in the overall market so that we can profit from the growth of the World’s economy”. Under this investment approach, we’ll start by picking the index that reflects the overall market.

Second, we’ll pick the ETFs. Depending on the market index we choose, there will probably be several financial institutions offering at least one ETF that tracks that index. We’ll learn how to compare the ETFs offered and how to chose the one that best matches our preferences.

Lastly, we’ll pick our broker. Many criteria are involved in choosing a broker. One particularly relevant is naturally the price, which is typically composed of an annual fixed cost plus commissions on trades, and depends (in part) on the ETFs selected.

One last thing before we proceed. This is the moment where you start to be mostly on your own. I mean, you definitely have to make your own investment decisions. This is true since the beginning: you are completely entitled to disagree with the investment approach I suggest here and to choose a different investment vehicle. But more importantly, you should make your own judgment on the actual investment you’ll make. I’m posting here the investment I’ve made, but only as a reference to how you might make your own research and reach your own decision on the investment that is right for you. I don’t want to feel guilty one day for pushing you to a wrong investment. I’m not pushing you to anything. This is your call.

Step 1/3: Picking the Index

18 min read.

Before picking the market index you want your investments to be tied to, you have to define the market. Our investment approach states that we’re investing in the ‘World economy’, on the ‘general market’. But what does that mean? It means that we want to be diversified across industries and regions.

I don’t see any consideration to make about being diversified across industries. But there are three key questions to make about investing across regions:

- Emerging Markets tend to be riskier than Developed ones. How much exposure do I want to Emerging Markets?

- Inflation significantly eats into your real returns. How much should I weight my domestic market on my portfolio to mitigate the inflation risk? What is “my domestic” market as a Euro citizen?

- When you invest in assets abroad, you’re exposing yourself to exchange rate risk, meaning the risk of having your portfolio’s value decrease by a change in the currency exchange rate during the time you hold foreign assets. How much should I weight assets expressed in foreign currencies in my portfolio?

Let’s discuss each point at a time.

Exposure to Emerging Markets

Both for economic and political reasons, investing in Emerging Markets (often referenced as EMs) such as China, India, and Brazil is riskier than investing in Developed Markets (DMs) like the UK, Germany, France, and the USA (although with Trump’s tantrums, one can argue that it’s quite risky to invest in the US nowadays).

To mitigate this risk, you probably don’t want to be too exposed to EMs. Review Swensen’s Model of Asset Allocation here. You’ll see that only 5% of his suggested portfolio is on EMs, compared to a 45% exposure to Developed Markets.

For now, and the next few years, I’m not investing in EMs at all.

Inflation and Real Returns

There’s a great article about the impact of inflation and exchange rates on bogleheads, a highly acclaimed blog on personal finances, and I advise you to read it. I’ll simplify the major points to introduce you to this issue.

Inflation is the general rise in prices. Investopedia should be able to explain to you what inflation is and how it works. Basically, if in the previous year, you could buy a month’s worth of goods (food, gas…) and services (rent, water, gym…) with 1.000€ and meanwhile inflation was of 2%, then you’ll have to pay 1.020€ to get the exact same amount of goods and services. In “nominal terms”, meaning just looking at the number, 1.020€ is higher than 1.000€, but in “real terms”, meaning the value behind the number, 1.020€ today is equivalent to 1.000€ one year ago.

Company profits tend to follow inflation. If inflation is the general rise in prices across all goods and services, then both a company’s costs (the goods and services it buys to produce the goods and services it offers) and prices should increase roughly by the amount of inflation. In other words, a company, verifying that its costs are increasing by 2%, will also increase its prices by 2% to keep the same profit margin. Its profits will, therefore, increase by 2%.

Now, since a stock’s price is nothing more than the price investors are willing to pay to earn their share of the company’s future profits (in the form of dividends), then if the future profits have increased, in nominal terms, by 2%, the price the investor is willing to pay for the stock will also increase by 2%, leading the stock to increase by the same amount.

The bottom line: a stock’s price tends to follow the inflation rate of the market(s) the company operates in.

So if a company mostly operates in your market, then there’s no big risk of your investment in that company to decrease in real value. When you withdraw your investment, it will have its real purchasing power intact. But, if you invest in a company that mostly operates in a different market, then there’s the risk that your local inflation rate is higher than the one affecting the stock, and so that your real returns have been eaten into by the difference.

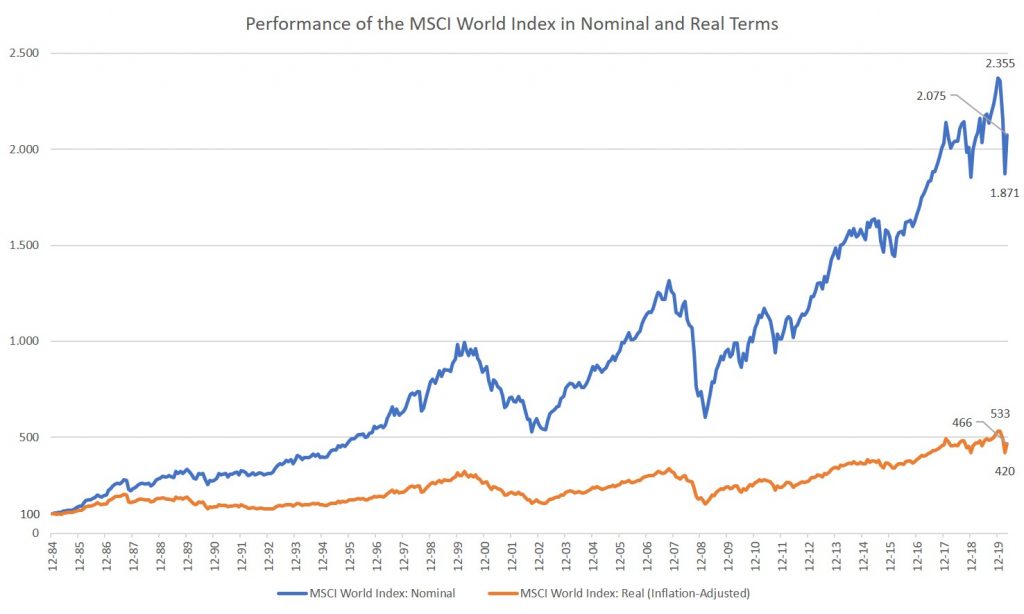

Just for you to have an idea of how much inflation eats up your nominal returns, take a look at the following graph.

You can download the excel used to produce the visualization above here: msci-world-nominal-vs-real.xlsx.

If you had invested 1.000 € in the MSCI World Index at the beginning of 1985 and held that investment for 35 years, you would have now 20.750€ (not considering annual fees and trading commissions). That’s almost 21x more! But in real terms, those 20.750€ in April 2020 are the equivalent of having 4.660€ in January 1985. Still, over 4,5x more than if you had just stored it under your bed, so no doubt investing was a good decision at the time. But real growth is always significantly lower than nominal growth, particularly in such a long time as we’re considering for this investment.

On the other hand, although inflation is a local phenomenon, there are reasons to believe that there won’t be dramatic differences between the inflation rates of Developed Markets (one reason to be careful in investing in Emerging Markets). In an increasingly global economy, factors that greatly affect inflation such as the price of raw materials should affect all countries somewhat evenly and Central Banks are doing a much better job at controlling inflation (see the bogleheads article mentioned above).

The bottom line: inflation risk is real and we should accommodate it in our investments by giving weight to domestic assets, which are more prone to follow domestic inflation. If you review Swensen’s Model of Asset Allocation above, you’ll see that he suggests splitting your Developed Markets investment into two: 30% domestic, and 15% foreign (plus 5% in EM).

In my investments, I’m not giving particular weight to the Portuguese or Euro markets for now. I’m just investing in the MSCI World index, which invests in each Developed Country market more or less according to that market’s weight in the World’s total capitalization (capitalization = number of stocks x prices of stocks). But I will tilt to domestic soon.

Currency Exchange Risk

The Problem

The issue with currency and exchange rates is in part similar to the issue with inflation. When you buy foreign assets denominated in a foreign currency, you indirectly have to convert the money you’re spending to that foreign currency, and only then you buy the assets. Then, you hold those assets in that foreign currency, and later, when you withdraw your investment, you sell the asset for its current price and convert that amount to your local currency. For example, a full-cycle investment in shares of Microsoft would entail:

- Converting your local currency (e.g. EUR) to USD.

- Buy the stock.

- Hold the stock denominated in USD.

- Sell the stock.

- Convert the sale value to your local currency.

Note that you don’t actually have to exchange currencies yourself. Your broker does this for you when you publish a trade order.

Evidently, the (nominal) return you get from this investment is determined by:

- The actual valuation in USD of the stock.

- The change in the exchange rate between your local currency and USD.

Consider this numerical example. You want to invest 1.000 € in Microsoft. The exchange rate at the date of purchase is 1EUR = 1,1USD, meaning that you have at your disposal 1.100 $ to buy shares of Microsoft. Microsoft’s shares are at 50 USD/share, so you buy 22 shares. When you want to withdrawal your investment, the shares are at 60 USD/share, a 20% increase, so you can sell it for 1.320 USD. However, while you held your shares, the Euro has appreciated against the USD. Now, 1EUR = 1,3USD. That means that your earnings from the sale equal to 1.015 €. From a stock growth of 20%, you only get 1,5%.

From this example, it becomes clear that exchange rates can impact greatly your returns. So it’s worthwhile to consider possible solutions to mitigating your exchange-rate risk. There are two main possibilities:

- Changing the index you follow: tilting your portfolio towards assets denominated in your local currency. The higher the weight of assets denominated in your local currency in your portfolio, the lower your exposure to other currencies is.

- Changing the ETF you buy: owning ETFs that are currency-hedged (see definition of “hedging” in Investopedia).

Solution A: Tilting Towards Assets Denominated in Our Local Currency

Naturally, if you want to reduce your portfolio’s exposure to assets denominated in foreign currencies, a solution is to allocate a higher weight of your portfolio to assets in your currency. So if you’re a European citizen, you’ll buy fewer stocks from Microsoft, Facebook, and other foreign companies and own more of European companies.

As you can see, exchange-rate risk poses as another argument to be worth considering having a tilt towards domestic assets in addition to the inflation risk, explained earlier.

The clear disadvantage is that you possibly would prefer to invest in foreign companies because you believe that their stocks are going to perform better than your domestic companies’ stock.

Solution B: Currency-Hedged ETFs

In this second solution, you’ll be able to put your money following the index that you want, regardless of its exposure to foreign currencies, while still limiting the exchange-rate risk. You can do this by owning a particular kind of ETFs called currency-hedged ETFs.

Although this solution fits bets in the next chapter, Picking the ETF, I’ll include it here so that we deal with the exchange-rate risk completely.

Currency-edged ETFs are less common than regular ETFs, but for the major market indexes, there should be several currency-edged on offer. By owning currency-edged ETFs, you’re still investing in the foreign companies that have their stocks denominated in a foreign currency, but you’ll be securing a fixed exchange rate in the future by which you can convert that foreign currency to your own. By fixing the exchange rate to a future date, you’re not exposed to the risk of it moving against you. And this is done by the fund itself – you don’t have to buy the financial instruments that allow you to fix a future exchange rate yourself.

Nevertheless, there are some drawbacks to this approach:

- Hedging is never perfect. Currency-hedged ETFs will help you mitigate the exchange-rate risk, but never completely cover it.

- Currency-hedged ETFs have higher annual management fees. Taking the example of the ETF I am currently buying, the regular version charges a 0,20% fee while the EUR-edged version charges 0,55%.

- The currency-hedged ETF’s tracking error tends to be greater than the error with the ETF’s regular version. The tracking error is the difference between the performance of the ETF and the performance of the market index it is tracking (there’s always a tracking error, we’ll see more about this later).

Why Ignoring the Currency Exchange Risk May Be the Best Solution

Both alternatives to mitigate the exchange-rate risk have drawbacks, making the decision of whether to hedge the risk or not trickier. If you search online (I suggest reading bogleheads 1, bogleheads 2, finiki.org and moneysense.ca), you’ll probably see that the general advice is the following: if you’re investing on the short/medium-term, hedge for exchange-rate risk, but you’re investing for the long-term, don’t hedge.

There are, in fact, solid arguments in favor of not hedging for currency risk when investing in the long-term. I’ll cover the two main here.

Time Cancels the Exchange-Rate Risk

First, take a look at the numerical example above again. See, it’s evident that the changes in the exchange rate affect greatly one single investment.

But the thing is that we’re not going to make one single investment. We’re going to put money into the stock market every 3 or 4 months for 30 years. During that time, we’ll buy foreign assets when the exchange rate is high, and we’ll also buy them when the exchange rate is low. Because exchange rates tend to hover around a particular value, unlike stocks that tend to grow endlessly, statistically, over the long term, the exchange rate effect will roughly cancel itself out.

See here the EUR:USD exchange rate over the last 20 years. It looks like it roughly hovers around 1,20 in a range of 0,60.

A Hedge Against Your Currency

The second argument goes as follows.

Naturally, the most important currency for us is our own, because most of our expenses are always going to be in our local currency (rent, electricity, everyday purchases of goods and services). This is why hedging against exchange rates seems like a good idea. Hedging attempts to guarantee the value of our investment in our currency so that it covers future expenses denominated in our currency.

But try changing your perspective. Having assets in other currencies actually hedges you against your own currency. See, most of our income is already denominated in your currency (salary, rents). What would happen if your currency suffers from a strong crash suddenly? What would happen if Portugal exits the Euro so that it can devalue its new currency to promote economic competitiveness, as was argued during the 2008 crisis?

I tell you what happens: you get fucked. Everything that is imported (which in the Portuguese economy consists of everything besides olive oil, wine, and cork) becomes suddenly much more expensive, and you’ll wish you had assets in other currencies that, suddenly, are worth much more their purchasing power. It’s a loss-loss situation where both your income and your investments decrease in purchasing power. If your investments were generating revenue denominated in foreign currencies (when you own stock you earn dividends), that revenue would help mitigate your domestic income’s loss in purchasing power.

If the opposite occurs, if your local currency suddenly grows in strength, sure your foreign investments and the revenue they generate will decrease in value when converted to your currency, but on the other hand, you’ll already be benefiting from the increased purchasing power of your domestic income denominated in your currency, currently stronger. It will be a loss compared to the situation where you had hedged your foreign investments, but you can’t have the loss-loss situation you can have when all your income is on the same currency.

The Bottom Line

I followed the advice I most read online and I did not currency-hedged my investments. Not only because of the drawbacks discussed above (full hedging being impossible, higher annual fees, higher tracking error) but also because I don’t find the case for hedging very compelling when investing for the long-run.

MSCI World: The Index I Chose

So, let’s review the main ideas that will affect our choice of the index we’ll track:

- It’s our defined strategy that we want to invest in the general market.

- Assets in Emerging Markets are riskier than Developed Markets, so exposure to EM should be minimized unless you’re available and willing to take that extra risk.

- It’s wise to tilt towards domestic assets, meaning assets that tend to follow your local inflation and that are denominated in your local currency, to mitigate the risks associated with inflation and exchange-rates.

- It’s not so important to have an active stance in mitigating the exchange-rate because time tends to cancel it and it can actually be good to have foreign assets to hedge you against your currency.

Taking the above points into consideration, I ended up examining the following indexes:

| Index | Geographic Focus |

| S&P Global 1200 | World |

| MSCI World | World excluding EM |

| MSCI ACWI | World |

| S&P 500 | US |

| MSCI EAFE | World excluding the US and Canada |

| STOXX Europe 600 | Europe |

| S&P Europe 350 | Europe |

| Euro Stoxx 50 | Euro Zone |

| PSI20 | Portugal |

Note that you can invest in the World market simply investing in an index with that focus, or by combining different indexes. For example, the US has a weight of 64% in MSCI World. If you want your exposure to the US to only be 50%, instead of investing on MSCI World you can allocate half your investment to the S&P 500 and the other half to MSCI EAFE.

You can see my analysis of these indexes here: index-analysis.xlsx. Once again, the indexes I analyzed are only a small set of those available. Others may be more aligned with your approach. You should do your own research.

Note

You should take an analysis of past performance with a grain of salt for three reasons:

First, because we’re investing in the long-term, it’s only relevant to analyze the past performance of an index or ETF during a long period as well. Analyzing its performance over the past 5 years will be misguiding because it doesn’t even cover a full economic cycle. At the very least, you should try to find data for the past 10 years, but 15 or 20 are ideal. However, finding long historical data is many times hard. I couldn’t find it. So I had to work with what I had.

Second, it’s quite difficult to have comparable data on different indexes. The data many times appear expressed in different terms (gross, net, total return, etc), which greatly impact the returns, and sometimes it’s difficult to know exactly how the data you obtained is expressed. When you have a choice on how the data is expressed, opt by total return because it assumes that dividends are reinvested back into the index, which is what we’ll do (more on this later).

Lastly, past performance does not guarantee future results. Really, analyzing past data only gets you so far. An index’s past performance is no indicator of how it will perform in the future. The S&P 500’s returns in the past 3 decades dwarf other indexes, such as the ones in Europe. Because the US economy has performed so well in the past, we’re used to thinking that it will continue to outperform other countries. But it may very well lag behind in the following decades. Who knows?

In the end, you’ll probably base your decision on which index(es) to track more on your investment strategy than on the indexes’ past performance. You’ll probably end up picking the indexes based on how much exposure you want to different geographies and industries.

I ended up picking only one index: the MSCI World. In my view, it has the broad approach I’m looking for in all axes – market cap, sector, and geography – following the stock of a total of 1650 companies, without being exposed to Emerging Markets. Later, possibly starting already next year (due to the Dollar-Cost Averaging approach I’ll discuss later), I’ll start to tilt towards stocks in Europe (investing in an index focused either on Europe or specifically the Euro Zone, I’ll have to do more research), but for now it’s only MSCI World.

A Quick Note About Ethics

When we invest in indexes, because they aggregate the stock of several companies, we lose control of the companies we invest in. We automatically invest in the companies that the index follows, regardless of whether we like or dislike their strategies and practices.

Here’s a list of the current top 10 constituents of the MSCI World index.

| Company | Weight in Index as of 31/04/2020 (%) |

|---|---|

| Microsoft Corp | 3,27 |

| Apple | 3,23 |

| Amazon.com | 2,35 |

| 1,15 | |

| Alphabet C | 1,03 |

| Alphabet A | 1,00 |

| Johnson & Johnson | 0,99 |

| Nestle | 0,87 |

| JPMorgan Chase & Co | 0,81 |

| Visa A | 0,79 |

Without even looking for them, I’m flooded with news and reports on seriously ill practices by Amazon, Google (Alphabet), Nestle, and Facebook just by surfing the web. And here they are among the top 10 companies incorporating the MSCI World Index. By investing in the index, I’m ultimately promoting these companies’ practices by increasing their share price.

Of course, companies pay more attention to the investors that are more discretionary with their investments, the ones that follow the news and read corporate quarterly reports and that move their investments accordingly. These are the ones the companies are trying to satisfy to retain their investment. For us, no matter what the company does, we’ll only disinvest from it (automatically) if it is removed from the index (MSCI World is reviewed quarterly to reflect changes in the underlying equity markets).

Still, there’s a ratchet at play to which we contribute by investing in the index. Discretionary investors put their money in these companies because their foul practices do generate returns, the companies’ capitalization gain significant weight in the total market, its stock becomes a candidate to be included in the index, and finally, when it is included, it automatically receives the funds of a pool of investors who had their money in the index. We’re ultimately promoting the practices that led the stock to be included in the index in the first place.

There is a solution though. Some indexes guide their choices on whether to include a company or not based on ethical rules, about their social or environmental impact for example. Candidates that abide those rules get to be included in the index and thus benefit from the investment of the index’s trackers, and those who don’t abide by the rules are excluded. You can opt to invest in these indexes instead.